[Films reviewed below include: The Apple ; The Silence ; The Terrorist ; My Name is Joe ; Eternity and a Day ]

The Apple, directed by Samira Makhmalbaf, the 18-year-old daughter of Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, was one of the festival's most remarkable works. The younger Makhmalbaf has chosen to reenact a real-life event, casting the members of the family whose story the film tells.

Neighbors in a poor part of Tehran have complained in a petition to the welfare department about a couple who have kept their two daughters, now 12 years old, locked up their entire lives. They have never been out of the house, they haven't had baths in years. The neighbors ask the authorities to take urgent action.

The welfare department takes the girls away, cuts their hair, bathes them. The first time we see Massoumeh and Zahra Naderi they can barely speak or walk, they appear almost retarded. The father is an old man; the mother is blind, her face entirely covered by a headscarf. The authorities return the girls to their parents, on the condition that they not be kept indoors any longer. The father goes out, locking them in once more. When he returns, he sets about teaching the girls to cook rice. 'God made a woman for her to marry.' One of the neighbors who signed the petition comes by. 'You told lies, slander,' the old man tells her. He complains that the petitioners had said he chained the girls up, which wasn't true. The neighbor responds, 'There's no difference between being chained up and not seeing the sun for 11 years.' He says, 'I'm humiliated. I'm so angry. I won't forgive you. Nor will God.'

Eventually the social worker in charge of the case returns, and finding the girls still locked up, confronts the father. He is not a monster. His wife is blind, she can't look after the girls. What is he to do when he goes out to make some money? 'I can't let my family starve.' The social worker pushes the girls out into the street; they immediately bounce back in, like rubber balls. She remonstrates with the old man, 'They're so used to being locked up, that they come back.' She takes the key from the father, and leaves him locked inside the house. 'See how you like it.' The social worker borrows a hacksaw from a neighbor and gives it to the man, telling him to either saw through the bars of the gate or break the lock.

Meanwhile the Massoumeh and Zahra set off on their adventures. They may as well have been raised by wolves in the forest. An encounter with a little boy selling ice cream begins their education. Ice cream, apples, a watch--interesting things cost money in this world. They run into two other girls their own age who adopt them as playmates. One of their new friends talks a blue streak. She takes them here and there. Massoumeh and Zahra shuffle along, but they seem to be adjusting to life out on the streets. It doesn't seem to frighten them.

All the protagonists--the four girls, the social worker--end up at the old man's door. The social worker gives Zahra the key and asks her to unlock the gate. With some effort, she releases her own father. There are no recriminations. The girls tell their father, 'Come buy us a watch.' It's a fantastic sight, the four girls, two on each side, leading the old man down the narrow street, almost an alleyway. The blind mother stumbles out of the open door, not knowing what's going on. 'I'm scared. Help me get my children back.' A little boy lives opposite the family's house. He has an apple on a string he teases people with, pulling it out of reach when they grab for it. The apple brushes against the blind woman's head and face, irritating her. She reaches for it.

The summary doesn't do justice to the richness of the film. It has so many elements to it. Certain images stay with you. A hand reaching through bars trying to pour water on a flowerpot. The mother's hand gripping her daughters', one of them holding an apple, like handcuffs. One of the girls negotiating with the little ice cream seller from the top of the courtyard wall. Some of the images are simpler than others, perhaps too simple, but the overall effect is devastating.

On one level, the film is about women in Iran. The father says, 'A girl is like a flower. If the sun shines on her, she will fade.' Samira Makhmalbaf, in her notes, comments: 'For me, the subject was a pretext to try to understand how the street plays an important part in man's integration in society. Boys are allowed to play in the street, but girls are excluded.'

If this incident had happened in an American city, it would simply have been a police matter. Makhmalbaf's film, on the other hand, does not make the parents out to be villains. They imprisoned their children, but they loved them. They treated them badly, but they thought they were doing the best for them. The filmmaker wants to understand the event, not point fingers. She uncovers the circumstances. The family was poor, backward and isolated. The society is to blame. People need to help each other. Isolation will kill you. The girls have lived in a state of sensory deprivation. As the film proceeds, through their interaction with others, they start walking straighter, they begin to speak. Solidarity, community are everything.

The director writes that she wants to understand 'how the inhabitants of this neighborhood could not have been aware of what was going on right under their noses for so long.'

Real people, real lives, real bodies. This is the first thing that strikes you. Movies and television in the US insist on pretty faces, regardless of whether the individuals have any thoughts in their heads or anything interesting to say. It's quite a contrast.

There are so many other things. The blind mother is an enigma. At various points in the film one hears her muttering, cursing in the background. Her face is entirely hidden. She is not romanticized. She is imprisoned by her own ignorance, fear, physical blindness. In the end, will she take the world on too?

The film is an astonishing accomplishment. Where are the 18 year olds here who are making such films, or thinking about such things? The 'barbarous' Iranians, this nation of 'terrorists,' continue to make some of the most humane, civilized films around.

Samira's father, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, who wrote The Apple and edited it, also had one of his own films at the festival, The Silence. It is a parable, set in a village in Tadzhikistan, about art and its relation to life and society. Khorshid, a blind boy, works as a tuner of traditional musical instruments. He takes the bus to work each day, but gets distracted by the sounds of the city. His boss is becoming impatient and his mother desperately needs the pay he earns. Despite everything, only sounds and music mean anything to the boy.

As in his Gabbeh (1996), Makhmalbaf seems to be striving for a form that would go beyond naturalism and neo-realism, which he may feel restrict him, and probably do. It's not clear that he's yet found an adequate form for his themes. Nonetheless, the film contains several of the most exquisite images to be found in any of the festival's works.

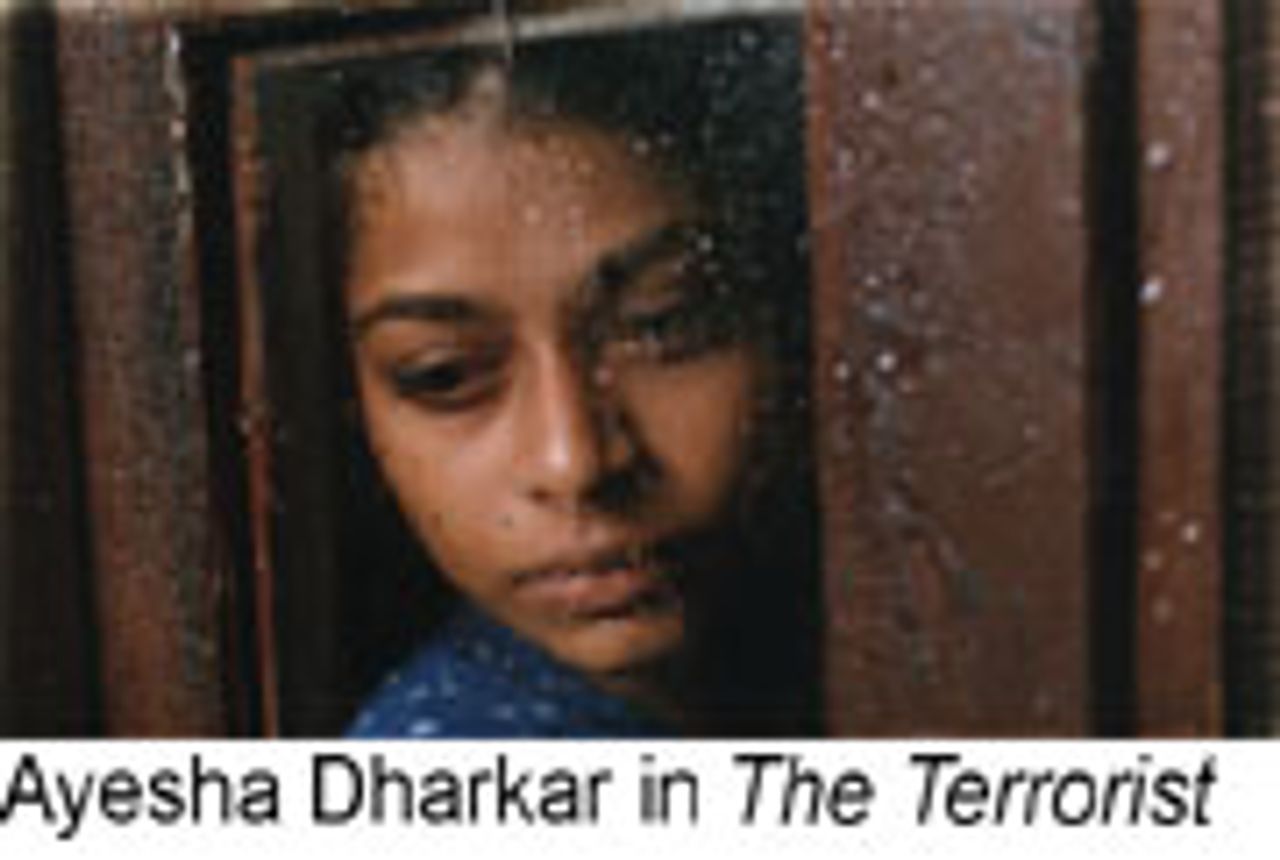

The Terrorist by Santosh Sivan is an honest and clear-eyed film from India, in Tamil, about a would-be suicide bomber working for an unnamed nationalist movement. The young woman, Malli, has come from a brutal background. Her brother has been killed by army repression. She has nothing, no education, no future. She adopts the same cause for which her brother gave up his life. 'The leader' explains her critical assignment, the assassination of an important political figure, 'a major obstacle to our movement.' She is to wear explosives on a belt around her waist and detonate them in the VIP's presence at a public ceremony.

The Terrorist by Santosh Sivan is an honest and clear-eyed film from India, in Tamil, about a would-be suicide bomber working for an unnamed nationalist movement. The young woman, Malli, has come from a brutal background. Her brother has been killed by army repression. She has nothing, no education, no future. She adopts the same cause for which her brother gave up his life. 'The leader' explains her critical assignment, the assassination of an important political figure, 'a major obstacle to our movement.' She is to wear explosives on a belt around her waist and detonate them in the VIP's presence at a public ceremony.

Malli makes her way from the jungle camp to the city where the suicide bombing is to take place. She takes up residence in the house of a farmer, pretending to be an agricultural student. His wife has been in a coma ever since their son died. The farmer and one of his workers are kind to Malli; they are a little eccentric, very lively. There are four days before the planned assassination. She discovers she's pregnant. She begins to have second thoughts. Her superiors tell her, 'Your sacrifice will inspire future generations,' but she wonders: 'Am I doing the right thing?' In the end, she proves incapable of pushing the button.

Sivan, a well-known cinematographer who has worked on the films of Mani Rathnam, among others, has made a film that strikes one as truthful within its limits. One could make the somewhat formal point that its criticism of movements of the LTTE variety remains at the level of liberal humanism, but that would seem to miss the heart of the matter. The film's portrait of Malli (played beautifully by Ayesha Dharkar), a girl with virtually no political or social understanding, willing to die unthinkingly 'for my country,' is fundamentally valid.

If the spectator were to draw the conclusion that any act of self-sacrifice is misguided, or that one ought to simply live for oneself, that would be another matter. That isn't the thrust of the film, however. Nor does Sivan show the army or the authorities in a positive light. He has made an objective, thoughtful work.

Insofar as The Terrorist demonstrates the inhumanity and thuggery of such movements, and makes clear that they offer no perspective for the layers of the population they claim to represent, it has a real value. (See the interview with Santosh Sivan and Ayesha Dharkar.)

My Name is Joe is one of the better films Ken Loach has made in recent years. One can make all the complaints against this film--the story of an ex-alcoholic, jobless man living in a tough neighborhood in Glasgow and his romance with a middle class health worker--that arise in the consideration of any of Loach's works, but it has numerous moving and truthful moments. One shouldn't ask for more from the filmmaker than he can deliver, but this is nearly as good as he gets.

Other 'left' filmmakers did not fare nearly so well. It's generally not a good idea to make direct links between art and politics. Some films, however, almost cry out for such connections to be drawn. Eternity and a Day, by Greek director Theo Angelopoulos, exudes the atmosphere of the exhausted, demoralized, impotent official European 'left.' A writer (Bruno Ganz) is about to go into the hospital for an operation on an apparently incurable disease. He wanders about, looks unhappy, visits his aged mother, comes to the rescue of an Albanian refugee boy, etc. Why have things turned out so badly, for himself and the world, he wonders? Why am I so helpless? Why have I led my life in vain? He takes a surreal bus ride. Someone with a red flag gets on, and then off. This is the level of it.

The film gets worse, more self-conscious and silly, as it goes along. The epoch with which Angelopoulos's hero apparently identifies himself so nostalgically was the heyday of the various reformist and Stalinist bureaucracies. One can see him marching in May Day parades, writing letters of protest, perhaps accepting a seat in parliament. Now all that has collapsed and Angelopoulos is sad. Permit some of us not to be.

Nanni Moretti's April is not much better. Where Angelopoulos is regretful, Moretti, an Italian leftist, is flippant. The rise and fall of the Berlusconi administration frames his work, a self-indulgent diary of a film. We see Moretti fretting about the 1994 election results, we see Moretti worrying about his impending parenthood, we see Moretti scrapping plans to make a film about a Trotskyist pastry chef in the 1950s, we see Moretti making a documentary about the election campaign of 1996, mostly we see Moretti.... In the end, he treats the electoral victory of the miserable center-left coalition that presently governs Italy as some extraordinary step forward. Some of the jokes Moretti makes are amusing, but the whole thing simply strikes one as superficial and complacent in the extreme.

Another Italian filmmaker, Gianni Amelio, treats the calamitous consequences of family obligations in The Way We Laughed. Set in the 1950s and 1960s, the film follows the relationship of two brothers from southern Italy making their way in Turin. One is the laborer, the other the student. In fact, this division of labor proves their undoing. Amelio brings out the suffocating and impossible character of this family structure, but the film never comes to life as much of a drama or a human tragedy. The characters simply get on one's nerves.

The Taviani brothers ( Padre padrone, Kaos) have made an interesting work, Tu ridi ( You laugh) based on two novels by Luigi Pirandello. In the film's first part, set in Mussolini's Italy, Felice, a baritone forced to become an accountant because of a heart condition, is driving his wife crazy by laughing in his sleep. It is quite eerie. Eventually she leaves, convinced he's dreaming of another woman. He can't remember what he is dreaming about. At work, he and his crippled coworker are tormented by a tyrannical boss. A doctor tells the former singer that because he is miserable in life, he is happy in his dreams. It's a form of compensation.

Nothing could be further from the truth, of course. When Felice is finally able to recall one of his dreams, it is a very unpleasant and sadistic. When his friend commits suicide, Felice forces his boss at gunpoint to write a note apologizing for his previous behavior. Then he takes a taxi to the seashore, planning to drown himself. But he meets a lovely woman, with whom he sang in the past. At an impromptu concert in a restaurant, he sings a Rossini aria that once made his name. In the end, he drowns himself anyway. Perhaps out of regret, or the sense that he has wasted his life trying to save it. A story about impossible choices.

The second part of Tu Ridi concerns a kidnapping, or, rather, two kidnappings. A young boy is being held prisoner in an empty mountain inn, on the friendliest terms, by a middle-aged man. The man has brought a computer for the boy to use; they play soccer; they eat whatever they want. One learns that the older man is a gangster, an associate of the boy's father who is being held by the authorities and may spill his guts any day. The boy is leverage against this possibility.

Another kidnapping had taken place a century before in this same locale. It is now recounted in a flashback. A doctor was seized by three armed men and taken to a hut in the mountains; they wanted ransom from his family. The doctor explains that his family doesn't give a damn about him, they are only waiting for him to die. He recognizes his kidnappers, three brothers. The following morning their father appears. 'We can't kill you, or set you free.' The doctor is forced to spend his remaining days with these poor people in the mountains. They strike up a relationship. In the course of various conversations, the doctor, apparently an enlightened man, explains a variety of scientific facts to these uneducated people, about the nature of the solar system, about gravity, about the speed of light. At first they're skeptical, but he makes an impact. One couple names their baby Galileo in honor of his explanations. The doctor gets something from them too, becoming part of a community, playing with the children and so on. He dies a natural death and they all mourn him.

We return to the present. From newspaper headlines we learn that the boy's father has turned informer. The kidnapper, who performs a peculiar martial arts/dance routine as exercise, brutally kills the kid without a second's hesitation. This story is clear enough. The 'savage' past, with its gun-wielding, masked peasant-bandits, proves to have been less alienating than the present, with its computers and 'New Age' gangsters. The film is compellingly made.

Two films from South America were as noteworthy for what they seem to suggest about a change in mood as for their artistic contributions. Neither Clouds by Fernando Solanas ( Hour of the Furnace) of Argentina nor Central Station by Brazilian Walter Salles represented an extraordinary aesthetic breakthrough. But they were intelligent, coherent efforts to grapple with various social, cultural and psychological problems. In recent years cynicism, demoralization and a general loss of bearings have dominated a great many South American films. The catastrophic defeats of the 1960s and 1970s, and the 'triumph' of free-market thinking in the subsequent period, had the most disorienting consequences, it appeared, for the artists on that continent. These new works hint at the emergence of a healthier, more critical cultural climate.

* * *

A final note:

In alphabetical order, these were the films I thought most interesting at the Toronto festival--DW.

The Apple, Samira Makhmalbaf, Iran; Autumn Tale, Eric Rohmer, France; Dance of Dust, Abolfazl Jalili, Iran; Dr. Akagi, Shohei Imamura, Japan; Flowers of Shanghai, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Taiwan; The Hole, Tsai Ming-liang, Taiwan; Killer, Darezhan Omirbaev, Kazakhstan; Life on Earth, Abderrahmane Sissako, Mali; My Name is Joe, Ken Loach, Britain; Pecker, John Waters, US; The Silence, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Iran; The Terrorist, Santosh Sivan, India; Tu Ridi, Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, Italy; West Beirut, Ziad Doueiri, Lebanon.

- Part 1: A comment on the 1998 Toronto International Film Festival

- Part 2:

Dr. Akagi ; Dance of Dust ; Flowers of Shanghai - Part 3:

Killer ; 2000 seen by ; Life on Earth ; Book of Life ; The Hole ; Trans ; Pecker ; Autumn tale - An interview with Tsai Ming-liang, director of The Hole

- An interview with the director, Santosh Sivan, and leading actress, Ayesha Dharkar, of The Terrorist

See Also:

On what should the new cinema be based?

[17 June 1996]