On the evening of May 4, 1886, thousands of workers gathered in Chicago’s Haymarket Square to protest against the police killing of six strikers that had taken place a day earlier. As the rally wound down, a bomb exploded among a phalanx of policemen who had moved in to disperse the crowd. In the ensuing melee, seven policemen and an unknown number of civilians died.

The “Haymarket riot” triggered the first American red scare. Media reporting was one-sided and vitriolic. Even though most casualties resulted from policemen’s bullets, the event was used to condemn the labor movement and its cause. Authorities quickly moved to pin blame for the event on Chicago’s working class anarchist leaders, who were arrested, tried, and convicted in a case that made a mockery of jurisprudence.

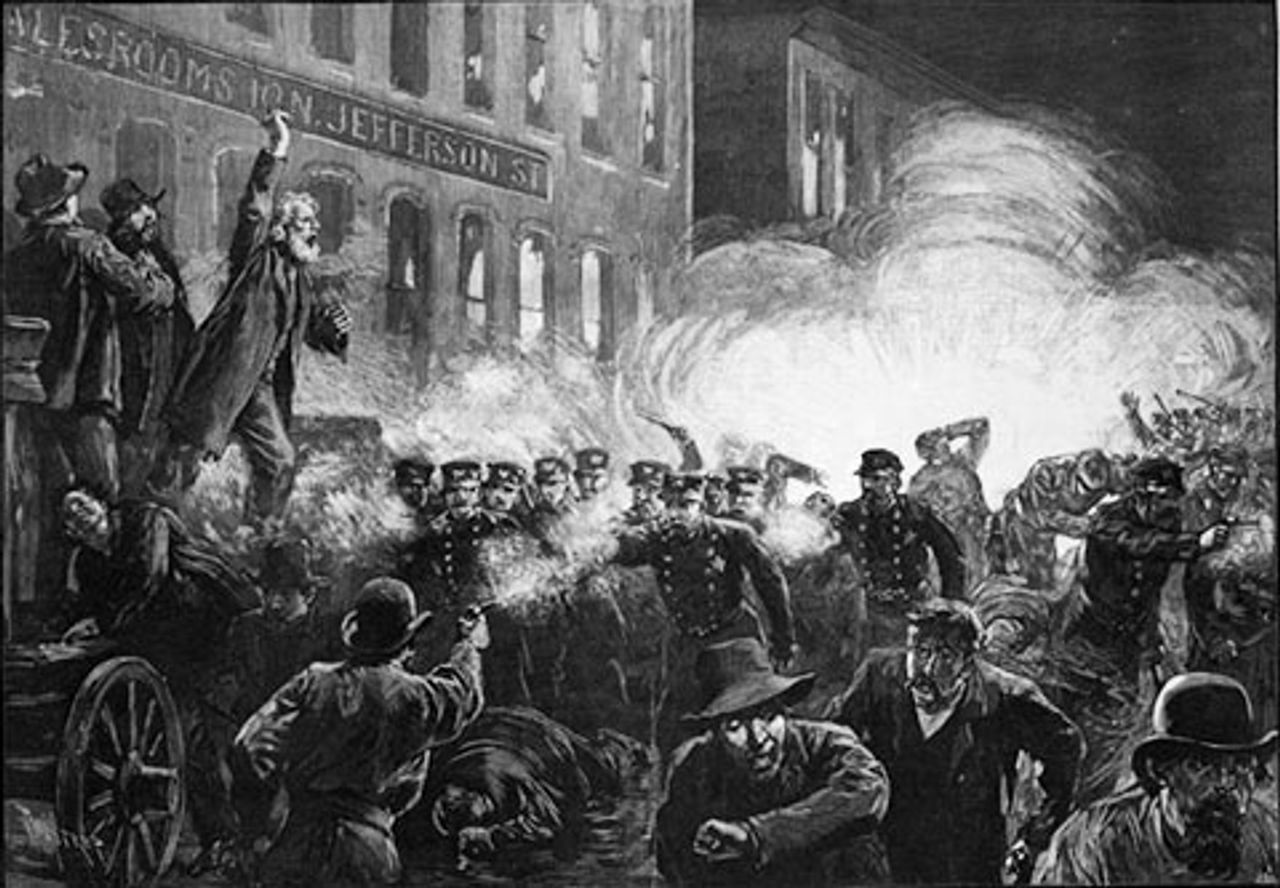

This image by Thure de Thulstrup, which ran in Harper's Weekly shortly after the Haymarket bombing, became the symbol of the incident, even though it inaccurately shows workers firing back at the police

This image by Thure de Thulstrup, which ran in Harper's Weekly shortly after the Haymarket bombing, became the symbol of the incident, even though it inaccurately shows workers firing back at the policeAfter the trial, an international campaign was waged for reversal of the death sentences, led by literary figure William Dean Howells, a close friend of Mark Twain. Of the eight defendants, four were hung on “Black Friday,” November 11, 1887: Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer and George Engel.

Haymarket is of enormous historical significance. It was the bloody culmination of the eight-hour-day movement, which had mobilized hundreds of thousands of American workers. And it was the direct origin of May 1 as the international holiday of the working class—celebrated virtually everywhere but in the land of its inspiration, the US.

In his Death in the Haymarket—The Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America, labor historian James Green presents the event in a broader historical context than earlier studies. He puts Haymarket at the center of the fledging workers’ movement, and shows how the event both expressed and deepened the class-consciousness of America’s industrial capitalists. Green persuasively argues that Haymarket defined class relations for decades to come.

In his acknowledgements, the author described the approach taken as “one that situated the event in a large social context and re-created the tensions and passions surrounding the first labor movement.” The most engaging aspect of the book is the detailed prehistory of the events of 1886, including descriptions of the major labor leaders and struggles.

As Green explains, Haymarket came in the midst of what became known as “The Great Upheaval” of mass working class struggle, which began with the thaw of winter in March of 1886. The lighting rod for these struggles was the demand for the eight-hour day, with workers rallying around the slogan, “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will!”

The workers’ tenacious struggle motivated the capitalists to unify their own efforts and defend their class interests with political, legal and police/military resources. In Green’s words, “Businessmen who had been ruthless competitors now joined hands to battle a ‘common danger’—a mass strike by workers who challenged the laws of political economy and who risked provoking bloody civil strife. So, in Chicago, as in New York, the Great Upheaval marked a crucial moment in what one historian called ‘the consolidation of the American bourgeoisie.’”

Green explains, “...the Haymarket case challenged, like no other episode in the nineteenth century, the image of the United States as a classless society with liberty and justice for all.”

The standpoint of Death in the Haymarket is that the experience of the Haymarket Affair was the outcome of struggles going back to the Civil War (1861-1865) and played a central role in the development of class-consciousness within the American labor movement. Green illustrates the widespread influence of the ideals of the young Republican Party in the working class movement as well asupon the many political figures who sought to shape postwar American society according to the ideals of Lincoln.

This “republicanism” unified competing social forces during the struggle against slavery. But in the two decades after the Civil War, industrial capitalism and class conflict shattered this unity, and with it illusions that the victorious Republic would reward workers’ with a fair share of their labor. Green writes:

In the years after Lincoln’s death...workingmen, the very mechanics who benefited most from the free labor system Lincoln had extolled, began to doubt the nature of their liberty. A few months before the war ended, the nation’s most influential trade union leader, William H. Sylvis, came to Chicago and sounded an alarm that echoed in many labor newspapers in the closing months of the war. The president of the powerful Iron Molders’ International Union excoriated employers who took advantage of the war emergency to fatten their profits while keeping the employees on lean wages. When union workers protested with strikes, politicians called them traitors, soldiers drove them back to work, and many loyal union men were fired and blacklisted by their bosses in retaliation. How, Sylvis asked, could a republic at war with the principle of slavery, make it a felony for a workingman to exercise his right to protest, a right President Lincoln had once celebrated as the emblem of free labor?... If the ‘greasy mechanics and horny-handed sons of toil’ who elected Abraham Lincoln became slaves to work instead of self-educated citizens and producers, what was to become of the Republic?

The beginnings of the eight-hour-day movement

Green explains the origins of the eight-hour movement in the war’s aftermath, when the agitational work of key working class leaders intersected with the movement of the masses. Green documents the efforts of Sylvis and Chicago labor agitator Andrew Cameron, publisher of Chicago’s The Workingman’s Advocate. Sylvis believed the eight-hour day would be the first step to the “social emancipation” of workers. Another working class leader, Ira Stewart, a mechanic from Massachusetts and a wartime abolitionist, led a popular movement that established eight-hour leagues across the country by 1866.

Green cites Karl Marx’s analysis of the eight-hour movement:

“...This postwar insurgency impressed Karl Marx, who had followed Civil War events closely from England. In 1864 he helped create the International Workingmen’s Association in London, whose founders hoped to make the eight-hour day a rallying cry around the world. The association and its program failed to draw a significant response from workers in Europe. Instead it was from the United States that the ‘tocsin’ of revolutionary change could be heard. ‘Out of the death of slavery, a new and vigorous life at once arose,’ Marx wrote in Capital. ‘The first fruit of the Civil War was the eight hours agitation,’ which ran, he said ‘with the speed of an express train from the Atlantic to the Pacific.’”

The movement achieved such influence that an eight-hour-day law was enacted in the state of Illinois by governor Richard Oglesby, a Radical Republican and friend of Lincoln, in March of 1867, to take effect the following May 1. When the day arrived, employers refused to abide by the law and in one week, effectively broke the movement by the use of force from police, militia and private agents. Workers would not forget.

Green gives a brief but significant description of the influence that the events around the Paris Commune had on the thinking of both the working class and the bourgeoisie of Chicago. In the summer of 1870, Chicago’s press closely followed the Franco-Prussian War. When the citizens of Paris denounced the armistice that was signed in January 1871 and stormed the Bastille, driving government forces back to Versailles, events were covered on a day-by-day basis, just as they had been done during the American Civil War. Initially, many Republican leaders identified with the citizens of Paris.

There was great sympathy in the immigrant population for the cause of the Communards, as many read Marx’s account, “The Civil War in France,” as it was published in English in serial form in Cameron’s newspaper. He cited labor advocate Wendell Phillips, “Scratch the surface...in every city on the American continent and you will find the causes which created the Commune.”

As the conflict deepened, press coverage shifted clearly against the Parisians, railing against “communists and atheists.” Some contemporary bourgeois commentators wondered if this could happen in American cities with their large immigrant populations of unknown views. Americans’ religious faith, it was proclaimed, would prevent a similar “godless outbreak in our cities.” The Chicago Tribune was hysterical. As Green describes, “...when the Commune’s defenses broke down on May 21, 1871, the Chicago Tribune hailed the breach of the city walls. Comparing the Communards to the Commanches who raided the Texas frontier, its editors urged the ‘mowing down’ of rebellious Parisians ‘without compunction or hesitation.’ “

That same year, the Great Chicago Fire broke out on the night of October 8. The conflagration destroyed most of industrial Chicago and its working class neighborhoods. Social divisions that had been intensifying for years reached a new level of class tensions. Some newspapers blamed the fire on American “Communard arsonists” who were determined to deliver a “scourge upon the queen city of the West.”

Following the Great Fire, socialist ideas won a significant following as a result of the protracted depression and anti-working class politics of the city fathers, including the wealthy Marshall Field, who advocated and funded the building of huge armories and beefing up the police force with the latest repeating rifles and even a Gatling gun. In 1873, an organization called the People’s Party, made up largely of immigrant socialists, ran and won in the municipal elections. However, as a political force, they were essentially impotent. They had no desire to “rock the boat” and within a year were easily dispensed with by the Chicago elite.

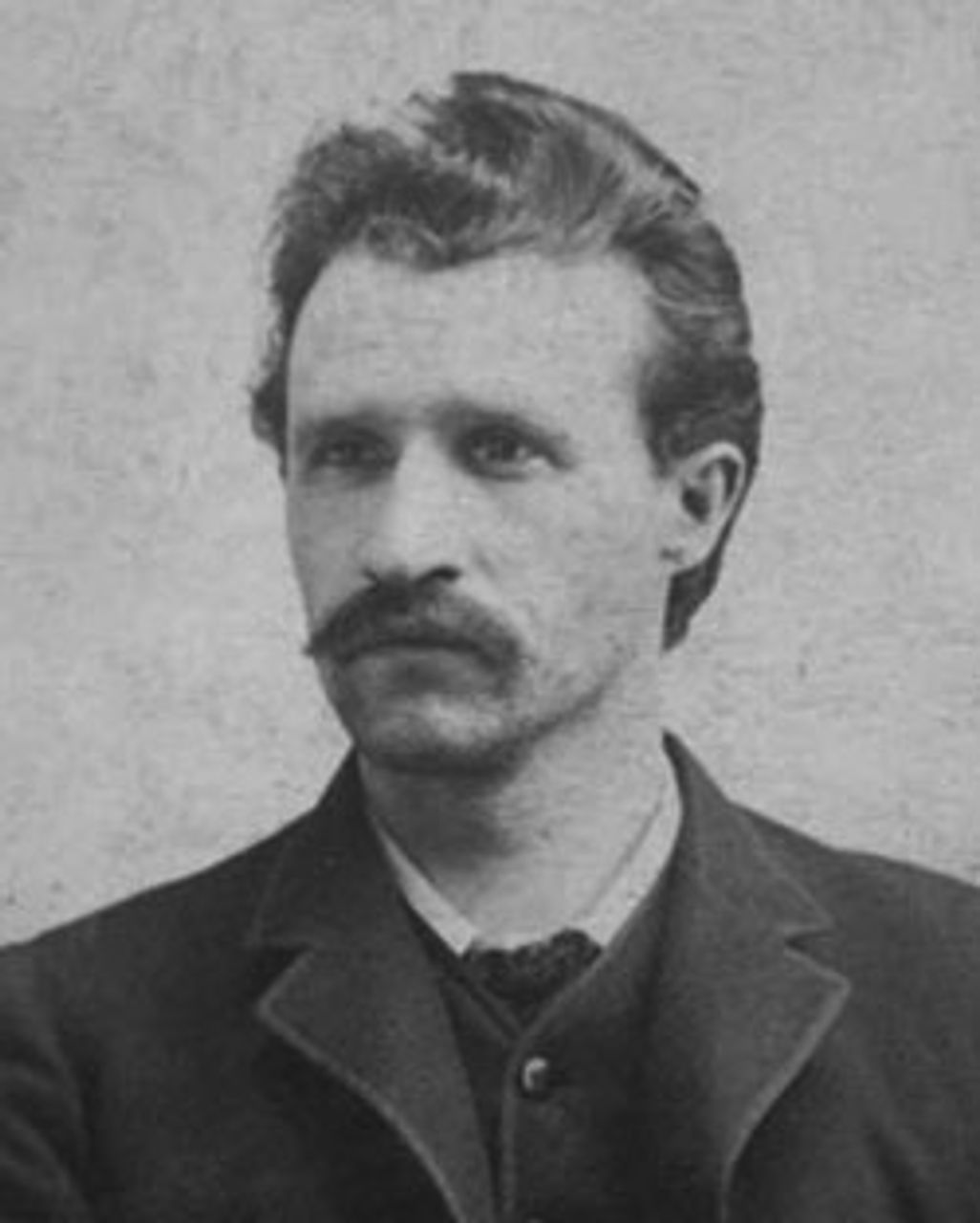

Albert Parsons

Albert ParsonsGreen pays particular attention to Albert Parsons and August Spies, the two most prominent of the Haymarket defendants, both of whom arrived in Chicago in the early 1870s, during the time when socialists of many different persuasions were getting a hearing in the city. Each of them was exposed to Marxism and became socialists within the same general timeframe.

New York labor activist Peter J. McGuire spoke as a representative of the International Workingman’s Association of Marx and Engels in 1876 to a Chicago audience that included Albert Parsons. Green describes this event as a turning point in Parsons’ life. With his great oratorical skill, the young Texan dedicated himself to the struggle to build the party, becoming the first English-speaking representative of socialism in Chicago.

August Spies

August SpiesLater, Parsons, Spies and many other socialist leaders came under the influence of Johann Most, a “firebrand” socialist turned anarchist, in the early 1880s. They joined his organization called the International Working People’s Party, affiliated with the “Black International” founded by the Bakuninists in the early 1880s in London.

Both Parsons and Spies were well-known and eloquent speakers for the cause of the working class. Along with a whole layer of Chicagoans, they immersed themselves in the struggles of the workers and activities of the socialist organizations as well as union organizations like the Knights of Labor and later, the Central Labor Union.

The “Great Trial”

Because they had distinguished themselves as the most able and active of the leaders of the working class—and the most dangerous to the employers—Parsons, Spies and six others were singled out for prosecution in the Haymarket trial. Hundreds of workers were arrested, questioned and many were terrorized and persecuted into becoming state’s witnesses. The prosecution publicly stated that simply being an anarchist was enough to establish guilt as a murderer.

Green devotes several chapters to the “Great Trial,” which began six weeks after the bombing, on June 21. Green clearly elucidates the details that contribute to the judgment of history that the proceedings were an out-and-out frame-up.

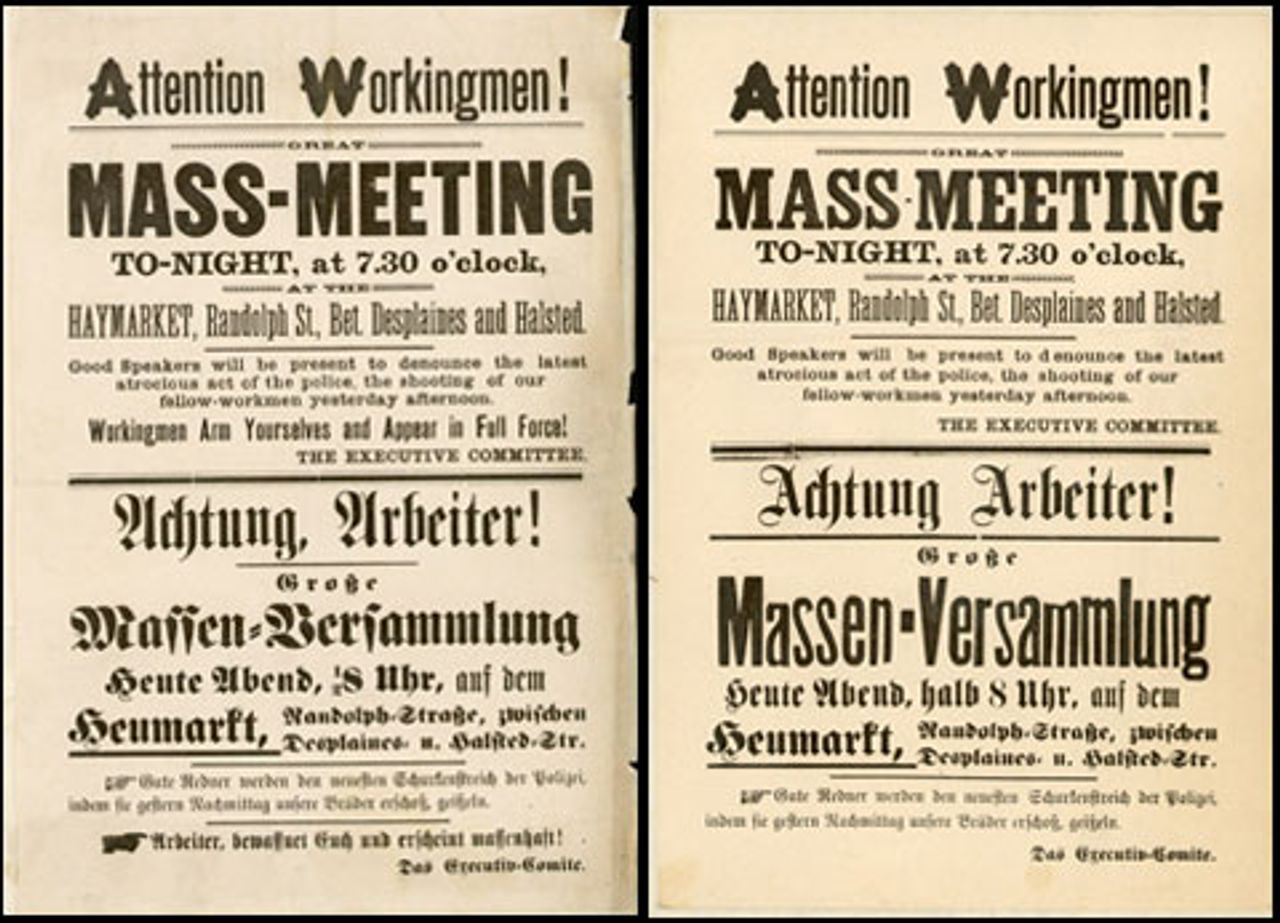

The version of the flyer for the Haymarket rally on the left was used as evidence by the prosecution even though August Spies stopped its printing and ordered the version on the right to be distributed instead

The version of the flyer for the Haymarket rally on the left was used as evidence by the prosecution even though August Spies stopped its printing and ordered the version on the right to be distributed insteadAfter the verdict and sentence by the stacked jury on August 20, 1886, the defense campaign began in earnest. It quickly spread to countries around the globe. In America, more than 100,000 signed the clemency petition circulated by William Dean Howells. Letters in support were sent to the Illinois governor from all over the world, including from such notable figures as Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw.

Green presents anecdotes illustrating how, after the hangings, the case of the “Chicago Martyrs” was embraced by workers all over the world. Yet he points out that in the years that followed, but for the tireless work of Parsons’ widow, Lucy, the experience of the Haymarket was at risk of being forgotten. The “Chicago Idea” espoused by the Haymarket defendants was not forgotten, however. In May of 1894, railroad men led by a young Eugene V. Debs crippled George M. Pullman’s rail empire as sympathy strikes spread everywhere west of Chicago. Debs went on to become the most popular American socialist leader of the early twentieth century.

Lucy Parsons attended the founding conference of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, which was held in Chicago, to appeal to the delegates to visit the martyrs’ tombstone and pay homage. She remained active in and passionate about the workers’ movement until her death in a house fire, in 1942.

Even though he presents a wealth of factual data about the many individuals and political parties that emerged in Chicago during that period, Green seems inclined to paint with a broad brush rather than clarifying differences between the diverse political trends in the nascent working class movement.

This weakness may have something to do with the author’s own political outlook, expressed most clearly in the last paragraphs of the epilogue, where he asserts that after the movement of May 1, 1886, “our industrial relations could have developed in a different, less conflicted way....” While Green is able to describe quite accurately the events of the day, he denies the historical necessity expressed by them.

Despite that, Death in the Haymarket is a valuable contribution to the study of this period and its importance to the history of the American and international labor movement.