Directed by Malik Bendejelloul

Searching for Sugar Man

Searching for Sugar Man

The documentary Searching for Sugar Man uncovers musical connections spanning two continents and more than 8,000 miles. The recordings of a Detroit singer-songwriter, Sixto Diaz Rodriguez (born 1942), who virtually no one ever heard of in the US, unknowingly achieved platinum album status (by the UK standard) in faraway South Africa.

Although a documentary, the film tells a story so incredible that it feels like a work of fiction. Searching for Sugar Man has been described as a fairy tale. To its credit, Malik Bendejelloul’s work raises numerous questions, some more profound than others, about music, global politics and money.

Stephen Segerman, a white South African eventually instrumental in tracking down the artist known only by his last name, Rodriguez, opens the story. He describes Rodriguez’s music as “the soundtrack to our lives,” speaking of his generation of Afrikaner youth who came into opposition against the apartheid system and police-state strictures aimed at repressing all independent thought.

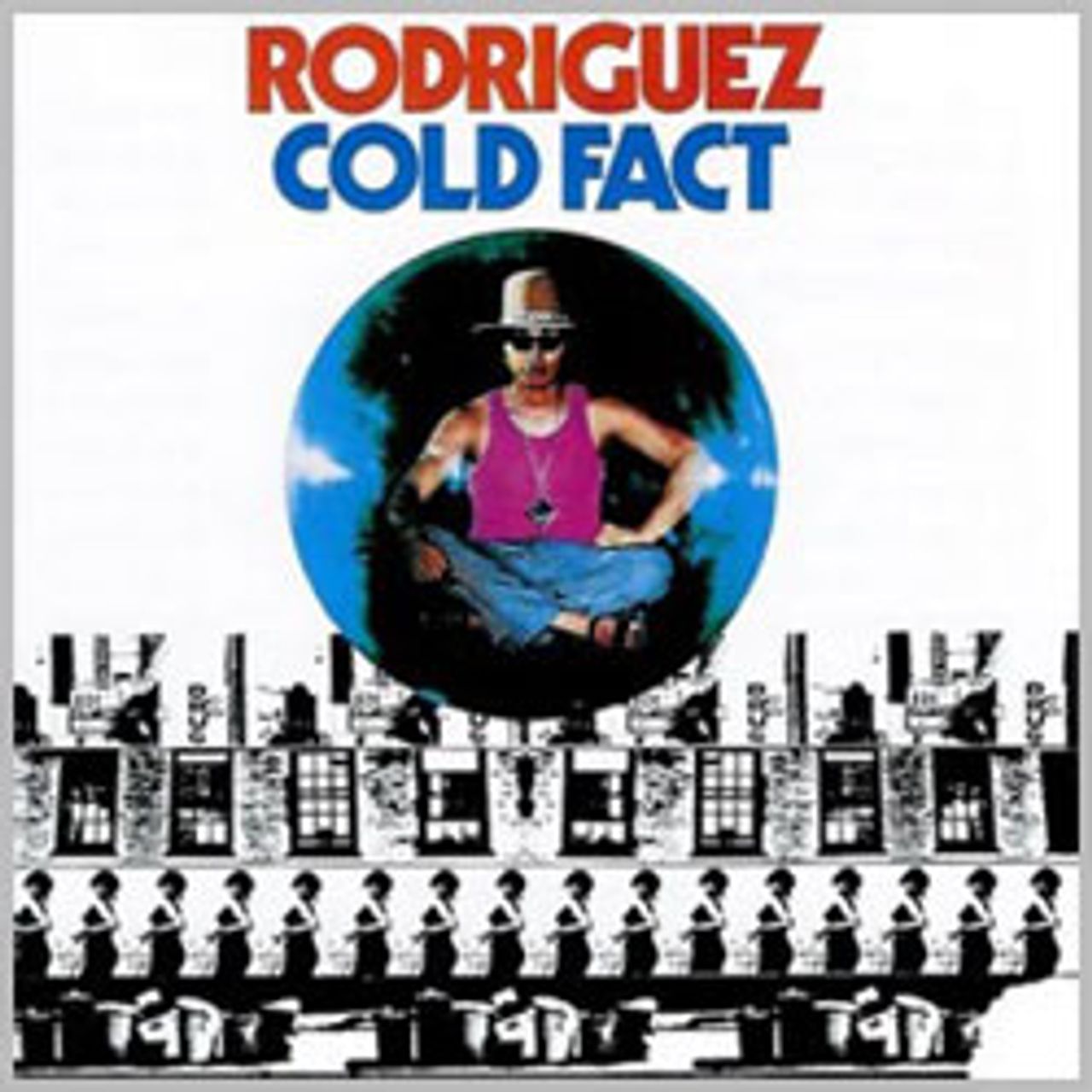

The music is compared to Bob Dylan’s, but in South Africa, according to Segerman, “Cold Fact,” Rodriguez’s first album, became so popular that it was one of three albums to be found in the record collection of virtually every white liberal household, along with the Beatles’ “Abbey Road” and Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Waters.” While his music is unmistakably influenced by Dylan, Rodriguez’s lyrics express more directly the experience of more oppressed layers of the population.

The music is compared to Bob Dylan’s, but in South Africa, according to Segerman, “Cold Fact,” Rodriguez’s first album, became so popular that it was one of three albums to be found in the record collection of virtually every white liberal household, along with the Beatles’ “Abbey Road” and Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Waters.” While his music is unmistakably influenced by Dylan, Rodriguez’s lyrics express more directly the experience of more oppressed layers of the population.

“Sugar Man,” the tune that inspired the film’s title, is a plea for drugs to escape from reality. Unlike Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man,” the tune doesn’t play up the ecstasy of a drug-induced psychedelia, but rather evokes a desperate inability in the face of a brutal world to find an “answer that makes my questions disappear.”

Another song from “Cold Fact,” entitled “This is Not a Song, It’s an Outburst: Or the Establishment Blues,” became an anthem to thousands of South African youth who defied the police and state forces. It evokes another Dylan song, “It’s All Right, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” but again it more explicitly criticizes the existing state of society. The last line cited below is the source of the album’s title:

Garbage ain’t collected, women ain’t protected

Politicians using, people they’re abusing

The mafia’s getting bigger, like pollution in the river

And you tell me that this is where it’s at

Woke up this morning with an ache in my head

I splashed on my clothes as I spilled out of bed

I opened the window to listen to the news

But all I heard was the Establishment’s Blues

Gun sales are soaring, housewives find life boring

Divorce the only answer smoking causes cancer

This system’s gonna fall soon, to an angry young tune

And that’s a concrete cold fact

Admirers in South Africa, where his recordings had become so popular, knew nothing about Rodriguez—where he came from, what inspired his music, not even his full name. It was believed that Rodriguez had killed himself onstage during a performance. There were conflicting rumors about his death—one said he poured gasoline over himself and ignited it; another story had it that he shot himself in the head with a handgun.

On the sugarman.org web site, Segerman (who ironically was also known as “Sugarman” or just “Sugar”) explains that in 1991 a chance conversation sent him searching for the second Rodriguez album, “Coming From Reality,” which was released in South Africa, but which he had never seen or heard.

Commissioned along with another writer to produce liner notes for the first CD release of that album, “we pondered the whereabouts of Rodriguez and asked if there were ‘any Musicologist detectives out there’ willing to help find this elusive man. Up in Johannesburg a journalist called Craig Bartholomew (Strydom) read those words, contacted me, and we met a while later in Cape Town and agreed to launch a joint search to find Rodriguez.”

Eventually, through a web site set up by Bartholomew-Strydom called “The Great Rodriguez Hunt,” the South Africans made contact with the producers of “Cold Fact” in Detroit.

They also found out that Rodriguez was still alive.

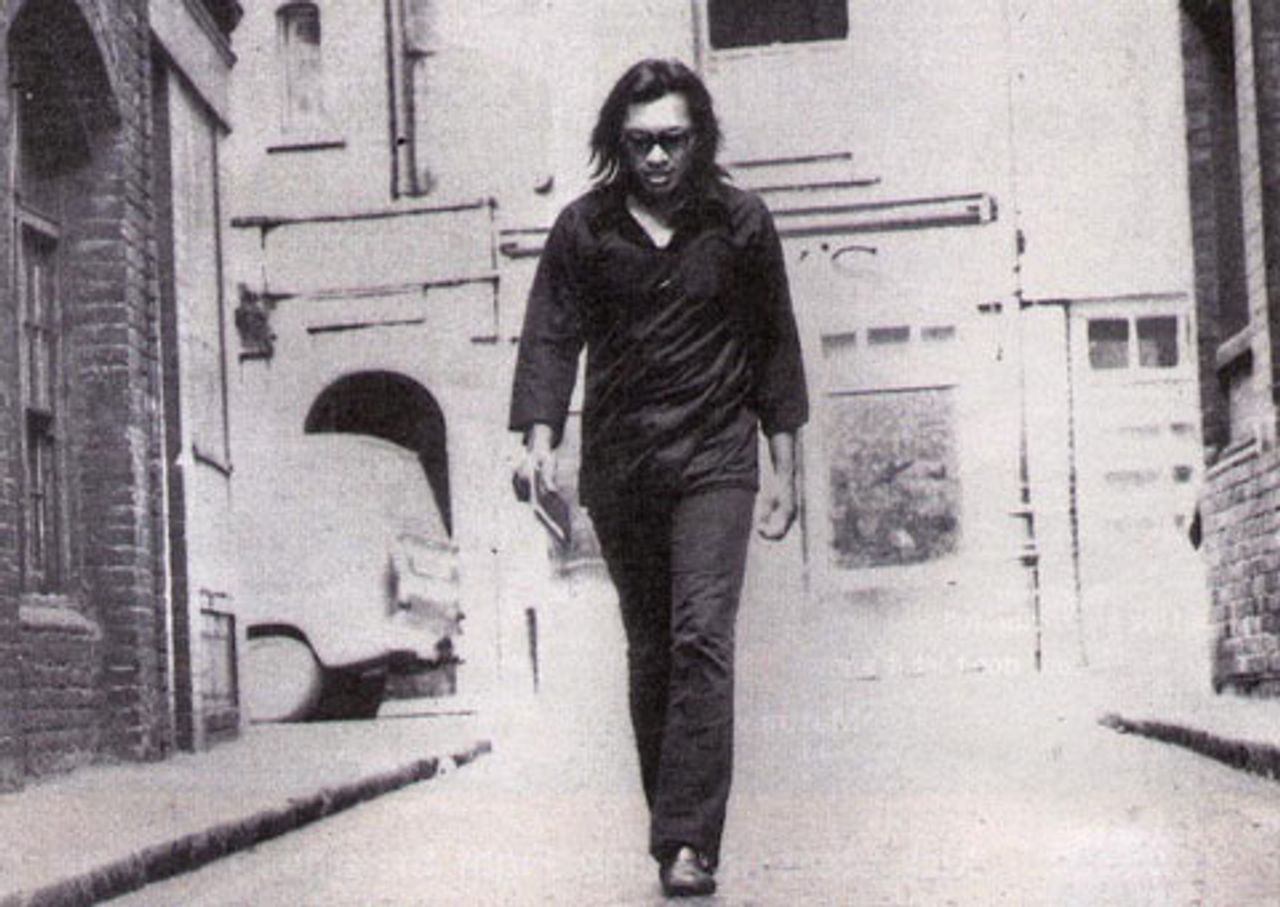

The first part of Searching for Sugar Man uses interesting animation techniques, based on director Bendejelloul’s sketches, to portray Detroit as it was and Rodriguez’s nomadic form wandering its streets. We first learn something substantial about Rodriguez from interviews with his three grown daughters. They describe their lives of poverty, and their father’s determination to provide them access to the best in culture.

After his albums failed to find a market and he was released by his record label, Rodriguez gave up on his musical career and continued his work in residential demolition and reconstruction. It wasn’t until his daughter responded to an appeal for information on “The Great Rodriguez Hunt” web site that she not only had seen Rodriguez, but that he was her father, that things changed. As a result of this contact, Rodriguez learned that he was “more popular than Elvis” in South Africa.

Quite notable is Rodriguez’s lack of bitterness when interviewed in the film. He considers himself lucky to have reached an audience. He and his daughter strike one as quite remarkable people.

In March 1998, the South Africans brought Rodriguez, along with his daughters, to Cape Town to begin a tour of the country. The venues were sold out. The film shows moving footage of his first concert, where the crowd was overwhelmed to see the artist whom they thought to be long dead.

How was it possible that so may copies of an album could be sold without the knowledge of the artist (or knowledge of the artist by his fans)? Bartholomew-Strydom explains that the classic adage “follow the money” led them to the owner of Rodriguez’s record company, Sussex Records. Clarence Avant, onetime chairman of Motown Records and known as the “godfather of black music,” founded the label in 1969 and owned it until it folded in 1975.

In a tense onscreen interview, Avant has little to say about Rodriguez’s popularity in South Africa, but becomes belligerent when the interviewer asks where the revenues for the album sales went.

Searching for Sugar Man opened this year’s Sundance Film Festival and received several awards. While it is well worth seeing, unfortunately, its availability is limited. In Rodriguez’s hometown of Detroit the film is being shown only at one theater and its run is over on Thursday.

Rodriguez’s albums are currently available on iTunes and Amazon.com. Rodriguez calls himself a “musico-politico.” He recently made several television appearances. The singer-songwriter is not in a hurry to make any new recordings, but if he does, one hopes that his newfound notoriety doesn’t dull the musical edge that made him so popular.